When I opened the first yellow cardboard folder full of poems, I had no idea what I’d find. That is still the case, though now I can make some guesses.

I did have a couple of vague assumptions, probably derived from comments by competition judges and editors, notably Helena Nelson who writes compellingly about her reading experience.

I’d assumed there would be enough very good poems to force some really difficult choices. That hasn’t happened yet, though there are enough to make me open every folderful with interest and in hope.

This may be because of the way we choose poems. We read and read, every now and then accepting a poem, until we’ve got enough for the next issue of the magazine. The winter issue is starting to fill up. So soon there may be a race between poems and time. It could go either way: we might have to turn down a few poems we like a lot because the magazine’s almost full, or accept a few we’re less sure of because it’s time to get the issue out.

I’d assumed there would be some imitation-Wordsworth and neo-Georgian poetry. There’s very little of either. Maybe those who would have written it are no longer here. Sometimes it’s fairly easy to tell from a submission what generation the writer belongs to, sometimes not. Not that I try to tell – it’s one of the many signals a poem can give out. (There’s more to say another time on who is sending in.)

Reading the poems is very enjoyable. I didn’t assume that. I was afraid of getting depressed by the sheer weight of poetry, and possibly also by its quality. Instead, I’m amazed and drawn in by the variety; the amount of thought, craft and creativity that’s out there. Also, I know what it feels like to print off some poems, address and seal the envelope, walk to the letter-box, take the next and irrevocable step…

Most poems are in free verse. The best show skill and a knowledge of contemporary poetry. They fly – take off in form and language, make new. Others are competently written. Quite a lot have not been worked on enough. Some read like diaries or postcards, with flat linebreaks that tend to go automatically with the syntax and do nothing to give the poem music or pace. Some are inchoate.

Specificity makes a connection with the reader. Abstractions / generalised descriptions have to be earned; and made new. All roads lead to Ezra Pound. This passage is to remind me, as both editor and writer, never mind anyone else:

Don’t retell in mediocre verse what has already been done in good prose. Don’t think any intelligent person is going to be deceived when you try to shirk all the difficulties of the unspeakably difficult art of good prose by chopping your composition into line lengths.

Against this background, striking subject-matter stands out, though if the poem hasn’t found its form etc then it won’t prosper. What’s important is often less the subject than getting a good angle on it; and making form, music, tone, language, metaphor all work together for take-off. I said ‘often’, because of course sometimes the subject matter is so original and/or engaging that it plays a part in a poem’s success. I can now see why poems with unusual content often win competitions.

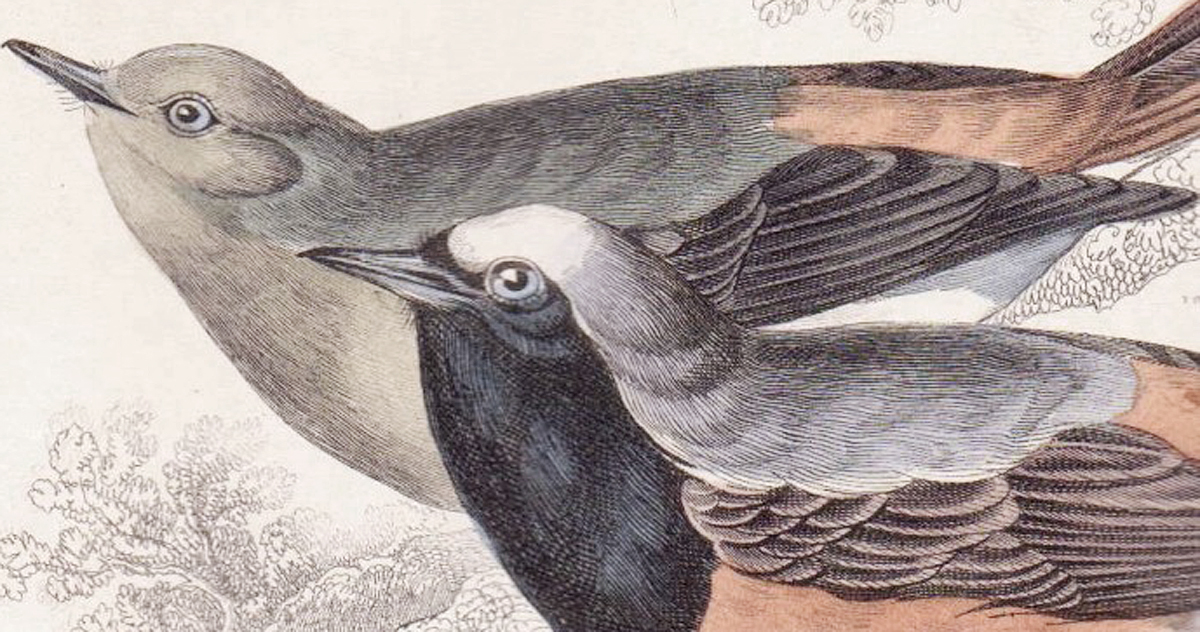

By the way, The Rialto gets sent plenty of bird poems, maybe chosen for bird-watcher Michael Mackmin, a few of which fly straight into the magazine. I’ve only seen two cat poems so far, maybe for the same reason.

It’s interesting to see whether the poems in a submission are similar or different in form. Sameness (except when it has a purpose, as in a series) can mean that the writer has a default mode and is not challenging him/herself. That’s a broad generalisation with many exceptions – the writer may have found a golden vein of form to exploit.

Since the two calibration exercises described in my last post, Michael has given Abigail Parry and me our own sets of poems, from which we’re bringing shortlisted ones to a meeting, with a view to reducing the backlog. To start with I read everything twice, with a gap in between – conscious that this was a luxury Michael, who gets dozens of submissions every week, couldn’t afford.

Now, for the first time, I’m reading most submissions once only. Then interesting and borderline ones a second time, and a third/fourth/fifth if necessary. (By the way, we are now reading poems that arrived in August, though Michael is still going through a few from May.)

I suppose this means I’ve gained confidence, which should be on the basis of having learnt something… After reading a lot, it’s easier (or at least, I think it is) to identify what stands out: is original, truly interesting and engaging; creates its own space on the page, and inhabits it; takes off. I’ve learnt not to judge a submission from the poem on top, because there may be a better one lower down. And points of detail from Michael, for example: if a poem has a quote as an epigraph, it mustn’t need to lean on the quote in order to stand up. I’ve also learnt from Michael – who’ll say at a meeting, That’s enough – to stop reading submissions as soon as my concentration level starts to fall.

I’m still haunted by a short, quiet poem that Michael spotted back in September when the three of us were all reading the same set of poems. It had passed me by. How many others have, or will?

Fiona Moore

On the principle that poetry is a way of life, not a living, I spent my £50 Cardiff prize on a train ticket to Wales for the ceremony; and how grateful I am that the laws of poetic physics dictated that my RSPB prize would not be crude lucre, but an unforgettable experience: a bird walk in Norfolk with top ornithologist and nature writer Mark Cocker, poet and RSPB officer Matt Howard, and

On the principle that poetry is a way of life, not a living, I spent my £50 Cardiff prize on a train ticket to Wales for the ceremony; and how grateful I am that the laws of poetic physics dictated that my RSPB prize would not be crude lucre, but an unforgettable experience: a bird walk in Norfolk with top ornithologist and nature writer Mark Cocker, poet and RSPB officer Matt Howard, and  Our last stop was Stub Farm, between Horsey and Hickling, where Mark led us to a platform lined with telescope- toting twitchers, all of us hoping to see cranes. But though we counted fifteen marsh harriers flapping one by one toward their nightly roost; a goldcrest; four twilit herons; and two magpies – first, as Mark remarked, ‘a poet’s magpie – one for woe’, then, to redeem us, ‘two for joy’ – the white stalkers remained elusive. Mark was disappointed for me, but I didn’t mind. For on this crisp, beautiful day I had felt a sense of belonging, not only to Norfolk, but to a long, passionate, gloriously eccentric tradition of people who value the natural world for its own sake: and in that vast and multifarious world there will always be a bird you hope to see next time. That is, if we can protect birds’ habitats, their food supply, and their irreducible Otherness – the absolute autonomy of wild creatures that paradoxically illuminates the most solitary and communal aspects of human nature too.

Our last stop was Stub Farm, between Horsey and Hickling, where Mark led us to a platform lined with telescope- toting twitchers, all of us hoping to see cranes. But though we counted fifteen marsh harriers flapping one by one toward their nightly roost; a goldcrest; four twilit herons; and two magpies – first, as Mark remarked, ‘a poet’s magpie – one for woe’, then, to redeem us, ‘two for joy’ – the white stalkers remained elusive. Mark was disappointed for me, but I didn’t mind. For on this crisp, beautiful day I had felt a sense of belonging, not only to Norfolk, but to a long, passionate, gloriously eccentric tradition of people who value the natural world for its own sake: and in that vast and multifarious world there will always be a bird you hope to see next time. That is, if we can protect birds’ habitats, their food supply, and their irreducible Otherness – the absolute autonomy of wild creatures that paradoxically illuminates the most solitary and communal aspects of human nature too.

12.39 – RD takes the following photo, and decides that it is an obvious but effective metaphor for the sort of feeling that the best sorts of poem can leave you with:

12.39 – RD takes the following photo, and decides that it is an obvious but effective metaphor for the sort of feeling that the best sorts of poem can leave you with:

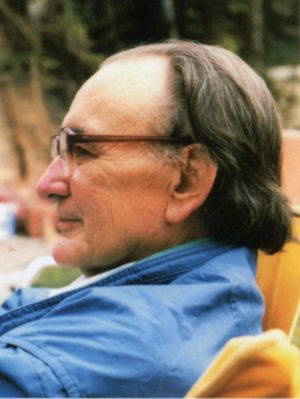

There’s something of a frisson going on about the fact that a ‘discovered’ new poem by Larkin turns out to be one that was written by another poet living in Hull, Frank Redpath.

There’s something of a frisson going on about the fact that a ‘discovered’ new poem by Larkin turns out to be one that was written by another poet living in Hull, Frank Redpath.